- Home

- Madeleine L'engle

The Young Unicorns

The Young Unicorns Read online

Table of Contents

Title Page

Introduction

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

GOFISH - QUESTIONS FOR THE AUTHOR

Copyright Page

For

all my friends at the Cathedral Church of St. John

the Divine, who are as the stars of heaven

for multitude and brightness,

and with the affectionate reassurance that with the exception of Canon Tallis and Rob Austin all the characters in this book are figments of my imagination. The Sub-Dean of the Cathedral reminds me that, in the author’s note to Murder Must Advertise, the late Dorothy Sayers wrote: “I do not suppose that there is a more harmless and law-abiding set of people than the Advertising Experts of Great Britain. The idea that any crime could possibly be perpetrated on Advertising premises is one that could only occur to the ill-regulated fancy of a detective novelist trained to fasten the guilt upon the most Unlikely Person,” and suggests that I might substitute Ecclesiastical for Advertising, and the United States of America for Great Britain, and thus have my own author’s note for The Young Unicorns. I would also like to remind my friends that the action takes place not in the present but in that time in the future when many changes only projected today may have become actualities.

Introduction

“Who are you in this book?” we would constantly ask our grandmother, Madeleine L’Engle, about every book that she wrote. Her books have protagonists that many people can identify with, generation after generation, whether it is the brave and clever, gawky and frustrated Meg Murry, or the vulnerable and awkward, but at the same time, sensitive and intuitive Vicky Austin. Madeleine also strongly identified with her characters, and said many times that she was both Meg and Vicky. There was so much that was recognizable as her and her life in her stories, and we wanted to be able to map her fiction to her biography, thereby fixing and understanding her place, and by extension, ours, in the family and the wider world.

Most children want to be told stories about themselves. We were no different, and so, reading the Austin books was always a special thrill, because the narrative is peppered with incidents and details that also featured in family lore, like the adorable malapropisms of Rob Austin and Vicky’s bicycle accident. The Austin family house in the quiet New England village of Thornhill (as described in Meet the Austins) is ever-present as a touchstone of their domestic peace, and is modeled on Crosswicks, a pre-Revolutionary War farmhouse in northwestern Connecticut where our grandparents and their children lived in the 1950s. The cross-country road trip in The Moon by Night copies the Franklin family itinerary of 1959, during which Madeleine started writing A Wrinkle in Time. In The Young Unicorns, the Austin kids unravel a mystery at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, where our grandmother was the librarian and writer-in-residence for more than forty years.

There is enough similarity of detail in the books to have caused us some confusion: If our grandmother is Vicky, how can she have the bicycle accident that left our own mother with a Y-shaped scar on her chin? If some of the details confounded our sense of reality, we never questioned the underlying truth of the characters and our grandmother’s relationship to them. If Madeleine were Vicky, then we felt understood. Because we were Vicky, too.

People would joke that Meet the Austins could have been called Meet the Franklins (Madeleine’s married name), and yet, we knew that Vicky and the Austins couldn’t be a simple translation of our grandmother’s life, because of the family tension and pain surrounding these books about this family. Madeleine’s own children were often shocked at how their own lives were appropriated and rewritten for publication, and felt judged against this very happy and practically perfect family. The line between fact and fiction can sometimes be blurry for writers, and the temptation to inscribe a certain version of and authority on events is strong.

All of Madeleine’s writing, fiction and nonfiction, was an example of how all narrative is fiction, and all fiction can be true. She wrote and lectured extensively on the difference between truth and fact, arguing that it is through story that we human beings approach the truth, not through facts, which can only get us so far. As her granddaughters, this was both liberating and confusing, but we happily suspended our disbelief, and some of our best-loved stories are ones that are culled from her real life, from her days in the theater, from her early years with our grandfather, and the mysterious decade of the fifties.

The five books that are now presented as The Austin Family Chronicles were written over a period of thirty years. A prolific writer of more than sixty books in a variety of genres, Madeleine created a web of characters that grew, changed, and surprised her. As we re-read these books over our lifetime, what strike us are the very different responses we have to this family. At eleven, we thrilled to the references to things that our mother or aunt or uncle would confirm were true. At seventeen, we were cynical about the blur between fact and fiction, and thought we could read our grandmother as if she were a book. In our mature adulthood, we recognize how rich and complicated our grandmother was, and that fact can be the springboard for fiction, and fiction can inform who we are and tell us about ourselves.

Charlotte Jones Voiklis and Lena Roy

March, 2008

One

Winter came early to the city that year. Josiah Davidson, emerging from the subway, his arms loaded with schoolbooks, shivered against the dank November rain which blew icily against his face and sent a trickle down the back of his neck. He did not see three boys in black jackets who moved out of a sheltering doorway and stalked him.

Uncomfortable, unaware, he hurried along the street until he came to a run-down tenement. Here he let himself in through the rusty iron gate that led to the basement apartment.

The three boys went silently up the brownstone steps and took cover in the doorway, listening, waiting.

The one room was dark and cold and smelled of cabbage; Josiah Davidson dumped his books on the table, sniffed with displeasure, and left. He stood for a moment on the wet sidewalk, looked downhill towards Harlem, uphill towards the great Cathedral which dominated the area, its multicolored Octagon of stone and glass glowing brilliantly against the rain-filled sky.

The three boys in the doorway waited until Josiah Davidson started up the hill, then followed. He climbed quickly and it was not easy to keep his pace. They began to run as he pulled a key ring, heavy with keys, from his pocket and fitted one into the wrought-iron gate at the bottom of the Cathedral Close.

As he opened the gate he swung round and saw them.

“What’s your hurry, Dave?” one asked.

“No!” he said sharply, pushed through the gate and slammed it in their faces.

They laughed mockingly, banging against the gate but not really trying to get in.

Dave ran up the hill past the choir buildings, through the Dean’s Garden, November-sad in the downpour, and climbed a flight of concrete steps that led into the Cathedral itself. The small side door was already closed for the night; he unlocked it and went into the ambulatory, a wide half-circle off which seven chapels were rayed like the spokes of a wheel. He could hear the high voices of the choirboys singing Evensong around the full length of the passage in St.

Ansgar’s chapel. He had once been a Cathedral chorister himself, but for the past few years the Cathedral had been mainly a short cut for him. He hurried down the echoing nave, past the soaring beauty of the central altar. Above it, the great Octagon seemed to brood over the Cathedral, protecting it for the night. One of the guards, strolling up the center aisle, saw the boy and waved: “Hi, Dave.”

Dave waved back but did not slacken his pace. From the chapel came the clear notes of the Nunc Dimittis: Lord, now lettest thou thy servant depart in peace, according to thy word …

—That’s all I want, the boy thought,—a little peace. And to have my past leave me alone.

He pushed out the heavy front doors and ran down the steep flight of stone steps that led to the street.

Josiah Davidson walked quickly along Broadway, stepping out in the street to avoid a cluster of darkly beautiful women looking cold in their saris, too delicate for the November air. He brushed by a group of men in native African dress, pushed through strolling Columbia students in assorted eccentricities of clothing. He was so accustomed to the conglomerate and colorful crowd on the Upper West Side of the city that it would have taken someone beyond the bounds of the merely unusual to have made him pause and take notice.

He halted at a large school building. Its bright lights spilled warmly onto the street; the heavy rain had slackened, was only a fine drizzle, but he felt cold. He turned up the collar of his coat and blew on his fingers. He looked up and down the street, but the three black-jacketed boys were nowhere to be seen. He leaned against the school building and watched boys and girls of all ages begin to straggle out the side door; classes had been dismissed an hour before, but older children had stayed for orchestra rehearsal, for detention, for club meetings; younger ones with working mothers had remained for supervised play until they could be called for. Some carried violin or clarinet cases, some satchels of books, and some, despite the icy wind blowing in from the Hudson, were eating ice cream. One of the senior boys, about Dave’s own age, called, “Emily’ll be along in a minute, Dave. She’s helping that little kid get his boots on.”

“Okay. Thanks.” Dave shoved his cold hands into his pockets, slouched against the cold wall of the school building, and waited.

Across the street a man in a dark overcoat and a foreign-looking fur hat stood in the doorway of an apartment building, watching the school, watching Dave.

“We’re here, Dave!”

Dave turned to the opening door; a little boy in a navy-blue pea jacket and a bright red woolen cap appeared. Behind him, one hand on his shoulder, came a tall, long-legged girl; her dark hair fell loosely on a wine-colored velvet coat which was in marked contrast to the plain navy blue everybody else was wearing.

“Emily!” Dave demanded. “Do you know what you have on?”

She bristled. “My good coat. My school coat’s still sopping.”

“Okay. So how was orchestra rehearsal?”

She relaxed. “Horrendous. Ear-splitting. Cacophonous. And if they don’t get the auditorium piano tuned I’ll have to do it myself. Hurry, please, Dave. I’ll be late for my piano lesson again and Mr. Theo’ll slaughter me.”

The man in the fur hat left the shadows of the doorway and followed the oddly assorted trio: the dark, shabby boy; the definitely younger and rather elegant girl; and the fair little boy who couldn’t have been more than seven or eight years old.

They reached the corner and turned down Broadway. The bitter wind whipped a few brown leaves and bits of soiled newspaper across the sidewalk. Strands of Emily’s fine, dark hair blew across her face and she pushed it back impatiently. As they passed a shabby little antique shop with a gloomy bin of oddments on the sidewalk in front of the dusty windows, Dave paused.

“It was here,” Rob said. “Right here.”

Emily pulled impatiently at Dave’s arm, but the older boy stood, looking at the shop window, at the door with the sign PHOOKA’S ANTIQUES, then moved on, more slowly.

Shortly before they reached 110th Street the man with the fur hat pulled ahead of them and merged with a group of people clustered about a newsstand. He held a paper so that he could look past it at the children as they came by.

The little boy, who had made friends with the crippled man who owned the newsstand, looked up to wave hello. His mouth opened in startled recognition as his eyes met those of their follower. He didn’t hear the news vender call out, “Hi, Robby, what’s up?”

The man in the fur hat smiled at the small boy, nodded briefly, rolled up his newspaper, and turned back in the direction of the Cathedral.

Dave and Emily had gone on ahead. Rob ran after them, calling, “Dave! He’s the one!” He tugged at the older boy’s sleeve.

“Who’s what one?” Dave pulled impatiently away from the scarlet mitten.

“The man we saw yesterday, the one who talked to Emily!”

Dave stopped. “Where?”

Rob pointed towards the Cathedral.

“Wait!” Dave ran back round the corner.

“Emily, he was the one,” Rob said. “I’m sorry, but I know he was.”

“I don’t want to talk about it.” Emily’s face looked pale and old beyond her years. She was just moving into adolescence, but her expression had nothing childlike about it. “It couldn’t have been the same one,” she whispered.

“But he was real,” Rob persisted. “It did happen.”

Dave returned. “I didn’t see anybody. Anyway, how do you know he was the one?”

“Because he had no eyebrows.”

Emily gave a shudder that had nothing to do with the cold. “I don’t want to think about him. I don’t want to think about yesterday. Come on. Let’s hurry.” She took Dave’s arm.

Rob backed along excitedly in front of them. “He was right under the light. And he recognized me, too. He did! He looked right at me and nodded.”

“Rob!” Emily said sharply. “Not now! Not before my lesson.”

Dave steered her away from a group of jostling boys and hurried her down the street, past the light from the shops, from the street lamps, from buses crowded with people coming home from work. “I suppose your lesson’s going to be a knock-down drag-out fight all the way as usual?”

“Mr. Theo’ll be furious if I’m late, but I know that fugue inside out. As a matter of fact—” Emily relaxed again and burst into a pleased, expectant laugh.

“What?” Rob asked. “What’s funny?”

“Nothing. At least not yet. If you come along to my lesson you’ll see.”

“Anything for a laugh,” Dave said. “Give me your key, Emily.”

As they turned towards the Hudson, Emily reached inside the collar of the velvet coat and tugged at a chain with a key on it, tangling it in her hair as she pulled it over her head. “Here.”

On the corner of Riverside Drive stood a large and dilapidated but still elegant stone mansion. Dave opened the heavy blue door that led into a hall with a marble floor and wide marble stairs. At the back of the hall, double doors were open into a great living room dominated by two grand pianos. By one of the pianos stood a small old man with a shaggy mane of yellowing hair.

If he had been larger he would have looked startlingly like an aging lion. He let out a roar. “So, Miss Emily Gregory!”

“So, Mr. Theotocopoulos!” She threw each syllable of his name back at him with angry precision.

“Three times in a row you come to me late.”

Emily flung her head up, simultaneously unbuttoning her coat and letting it fall to the floor behind her. “How late am I?”

The old man pulled out a gold watch. Temper matched temper. “Remember, Miss, that I come personally and promptly to you, instead of making you come to my studio—”

“So I’ll come to your studio—”

“In my declining years I must still work like a hog. One minute too late is too many of my valuable time—”

“I couldn’t help it, orchestra rehearsal—”

�

�No alibis! And kindly pick up your coat and hang it up—”

“I’m going to!”

“—like a civilized human being instead of a spoiled rat.”

Emily reached furiously for her coat. “I’m not spoiled!”

“You are disrupted and disreputable!”

“Then so is Dave!”

“Emily! Be courteous or be quiet!” The old man sounded as though he himself were no more than Emily’s age. “I am fit to be fried.”

Emily grabbed the coat and rushed towards the hall, bumping headlong into the doorjamb. She let out a furious yell, echoed by her music-master.

“If you knock yourself out you think that will make me sorry for you? Hang up your coat and come sit down at the piano. And do not move without thinking where you are going.”

“Do I always have to think!” Emily shouted.

Rob, who had started automatically to help Emily, turned back to the room and sat on a small gold velvet sofa in front of a wall of bookshelves, the lower, wider shelves filled with music. “Do you mind if I stay?” he asked politely. “Sort of to pick up the pieces, you know, if there are any left.”

“Mr. Theo,” Dave said, holding himself in control, “there is a difference between mollycoddling her and—”

“Sit down!” Mr. Theo bellowed. “You are talking about a twelve-year-old girl, and I am talking about an artist. I will not let her do anything that will hurt her music. Now sit still and listen—if you have ears to hear.”

Shrugging, Dave stalked over to his favorite black leather chair by the marble fireplace.

Out in the hall by the coatrack, Emily managed to get her coat to stay on its hook; then, walking carefully but with the assurance of familiarity, she came back and sat down at one of the pianos. “Then why don’t you let me give a concert if you think I’m a musician?”

Mr. Theotocopoulos took her hands in his. “Why could you not come straight home from school? Cannot that so-called orchestra get along without you? And your hands are too cold to be of any use for music at all.” He began to massage her fingers. “You are too young for a concert. You would be not only a child prodigy, you would be a blind child prodigy, and people would say, ‘Isn’t she marvelous, poor little thing?’ and nobody would have heard you play at all. Is that what you want?”

Love Letters

Love Letters The Summer of the Great-Grandmother

The Summer of the Great-Grandmother A Wrinkle in Time

A Wrinkle in Time The Young Unicorns

The Young Unicorns Two-Part Invention: The Story of a Marriage

Two-Part Invention: The Story of a Marriage The Other Side of the Sun

The Other Side of the Sun A House Like a Lotus

A House Like a Lotus Certain Women

Certain Women Many Waters

Many Waters Camilla

Camilla A Ring of Endless Light

A Ring of Endless Light Meet the Austins

Meet the Austins Dragons in the Waters

Dragons in the Waters The Small Rain

The Small Rain The Moment of Tenderness

The Moment of Tenderness A Wind in the Door

A Wind in the Door Miracle on 10th Street

Miracle on 10th Street The Moon by Night

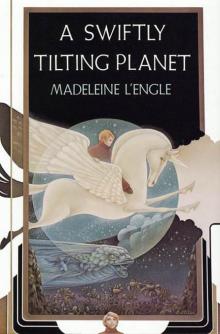

The Moon by Night A Swiftly Tilting Planet

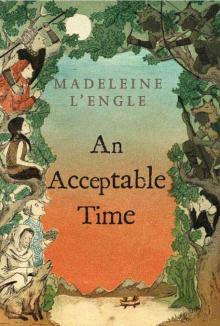

A Swiftly Tilting Planet An Acceptable Time

An Acceptable Time A Severed Wasp

A Severed Wasp The Irrational Season

The Irrational Season A Circle of Quiet

A Circle of Quiet A Live Coal in the Sea

A Live Coal in the Sea Troubling a Star

Troubling a Star Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art

Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art A Wrinkle in Time Quintet

A Wrinkle in Time Quintet Wrinkle in Time

Wrinkle in Time The Wrinkle in Time Quintet

The Wrinkle in Time Quintet Intergalactic P.S. 3

Intergalactic P.S. 3 Walking on Water

Walking on Water Bright Evening Star

Bright Evening Star The Rock That Is Higher

The Rock That Is Higher Madeleine L'Engle Herself

Madeleine L'Engle Herself The Arm of the Starfish

The Arm of the Starfish And Both Were Young

And Both Were Young The Twenty-four Days Before Christmas

The Twenty-four Days Before Christmas And It Was Good

And It Was Good A Stone for a Pillow

A Stone for a Pillow Do I Dare Disturb the Universe?

Do I Dare Disturb the Universe? Sold into Egypt

Sold into Egypt A Wrinkle in Time (Madeleine L'Engle's Time Quintet)

A Wrinkle in Time (Madeleine L'Engle's Time Quintet)