- Home

- Madeleine L'engle

The Twenty-Four Days Before Christmas Page 2

The Twenty-Four Days Before Christmas Read online

Page 2

“That’s true.”

“But I want you to see me!”

“I want to see you, too.”

“In the olden days people didn’t have to go to hospitals to have babies. They had them at home.”

“So they did,” Mother agreed. “But even if I had the baby at home, I couldn’t come see you being the angel.

“Why not?”

“Brand-new babies need a lot of attention,” Mother said, “and they can’t be taken out in the cold. I was pretty tied down at Christmastime the year you were born.”

“But I was born!” I cried. “And you were home for Christmas. You didn’t go off and leave John and Suzy alone. Oh, I forgot. Suzy wasn’t born. Anyhow, Mother, please could you ask the baby to wait till after Christmas?”

“I can ask,” Mother said, “but I wouldn’t count on it. What shall we do today for our Special Thing?”

“Let’s make the wreath for the front door.”

“Good idea. We’ve got lots of ground pine and berries left over, and I saved all the pine cones we gilded and silvered last year. When we get home you can run up to the attic and get them.”

On the sixteenth day of December John listened to the weather forecast before breakfast, and snow was predicted again. The sky had the white look that means it is heavy with snow. John and I were so pleased we ran almost the whole of the mile down the hill to wait for the school bus. A cold raw wind was blowing and we huddled into our parkas.

After school I had rehearsal. So did John, because he’s singing in the choir, and this is the first time that the cast of the Pageant and the choir have worked together.

I tried hard to walk the way I did with the Shu to Sub encyclopedia on my head, and to move my arms as though they were the graceful arms of a tree in spring and not the bare brittle branches of a tree in December. I remembered all my lines in my heart as well as my mind, and Mother had worked with me to make each word ring out clear and pure as a bell. Everybody seemed pleased, and John pounded me on the back and told me I was a whiz. The choir director congratulated me, just as though I were a grown-up, and told me that everybody was going to miss Mother in the choir, and I was forced once again to remember that Mother might not be home for Christmas. John asked the choir director if he thought it would snow, but he shook his head. “It’s turned too cold for snow.”

Mr. Irving, the choir director, drove us home and stopped in for a cup of tea. A big box of holly and mistletoe had arrived from our cousins on the West Coast, so John and Daddy hung the mistletoe on one of the beams in the living room.

After Mr. Irving had left, we opened the day’s Christmas cards the way we always do, taking turns, so that each card can be looked at and admired and appreciated.

John remarked, “Some people just rip open their cards in the post office. I bet the kids never see them at all. I’m glad we don’t do it that way.”

“Everybody’s different, John,” Mother said. “That’s what makes people interesting.”

“Well, nobody else I know does something every day during Advent the way we do. What’s our Special Thing for today?”

“Oh, I think the holly and the mistletoe’s plenty. Start setting the table, Vic. It’s nearly time to eat.”

The days toward Christmas flew by, and still there was no snow. And no baby. And rehearsals went well and I was happy about the way being the angel was going, and so was the director.

On the seventeenth of December we hung our collection of angels all over the house, and on the eighteenth we put the Christmas candle in the big kitchen window. On the nineteenth we made Christmas cards, with colored paper and sparkle and cutouts from last year’s Christmas cards.

On the twentieth day we put up the crèche. This is one of the most special of all the special things that happen before Christmas. Over the kitchen counter is a cubbyhole with two shelves. Usually mugs are kept in the bottom shelf, and the egg cups and the pitcher that is shaped like a cow on the top shelf. But for Christmas, Mother makes places for these in one of the kitchen cabinets. On the top shelf goes the wooden stable and the shepherds. Tiny wax angels fly over the stable. A dove sits on the roof. The ox and the ass and all the barnyard animals are put in, one by one, everybody taking turns. There is even a tiny pink pig with three little piglets, from a barnyard set John got one year for his birthday. There is a sheepdog and a setting hen and a grey elephant the size of the pig. Some people might think the elephant doesn’t belong, but the year I was born Daddy gave him to John, and he’s been part of the crèche ever since, along with two monkeys and a giraffe and a polar bear. Mary and Joseph will be put in on the morning of Christmas Eve, and then, when we get home from Church on Christmas Eve night, Daddy puts in the baby Jesus, and reads the nativity story from Saint Luke.

On the bottom shelf we put the wise men with their camels and their camel-keeper. We make a hill out of cotton, which is a little hard to balance the camels on, but when we’re finished it really looks as though the train of camels was climbing up a long weary road toward the Christ child. On Twelfth Night they’ll have finished their journey and will join the shepherds and the animals in the stable.

Last of all Daddy put the star up above the stable and fixed the light behind it. On Christmas Eve we’ll turn off all the other lights in the house, so all you can see is the lovely light from the star shining on the stable and the Holy Family and the angels and the animals.

On the twenty-first day of December we went with Daddy into the woods to get the Christmas tree. Mother stayed home, because she was feeling tired and heavy, but the rest of us tramped through the woods, including the dogs and cats. It was Suzy who found the perfect tree this time, just the right size and shape for the living room, with beautiful firm branches all around. Daddy and John took turns sawing, and we all helped carry it home, because the tree was tall, and heavy.

Daddy said, “Tomorrow’s Sunday, so we’ll trim the tree a little ahead of time to get it ready for Santa Claus and to make sure Mother’s here to help.”

John asked, “You really don’t think the baby’s going to wait till after Christmas, Daddy?”

“I rather doubt it. Every indication is that this baby is going to be early. Now, kids, we’ll put the tree carefully into the garage until tomorrow.”

That night I woke up, very wide awake. I knew it wasn’t anywhere near morning because the light was still on in Mother and Daddy’s bedroom. After a few minutes I got up, softly, so as not to wake Suzy. I put on my bathrobe and slippers and tiptoed down to the kitchen. The dogs came pattering out to meet me, wagging their tails. One of the cats meowed at the head of the cellar stairs. I put my finger to my lips and said, “Shh! Everybody go back to sleep.”

It wasn’t quite dark in the kitchen because the embers in the fireplace were still glowing, and the night-light was on. Mother and Daddy must have gone up to bed just a little while ago. I tiptoed over to the crèche, climbed on one of the kitchen stools, and turned on the light behind the star. The manger was empty, waiting for Mary and Joseph and the baby. They were still in their white cardboard box. I opened the lid and looked in, then closed the lid and put the box back.

Instead of feeling all full of anticipation the way I usually do, I felt heavy. I thought—I don’t want Mother to be in the hospital for Christmas. I want her to be home. I’d give anything if she could be home. But I don’t have anything to give. Anyhow, God doesn’t expect us to give anything in order for Him to love us. And least not a thing. Just ourselves.

I sighed again. And thought—Mother says we should never try to make bargains with God. That isn’t the way God works. But I’d give up anything, even being the angel, if Mother could be home for Christmas.

I sat looking at the empty crib in the stable until I got sleepy.

On the twenty-second of December when we were all home from Sunday school and church, Mother made hamburgers and milkshakes for lunch. Then Suzy and I helped with the dishes and Mother put on a carol record and we all sang “O Come, O Come, Emmanuel.” Daddy and John brought in the tree from the garage and set it firmly in a bucket of wet sand. The big boxes of Christmas decorations were brought down from the attic. First of all Daddy got on the ladder and he and John put on the lights, and the angel at the top of the tree. The angel is wearing white, with feathery sparkly wings; it’s the angel Mother used to copy my costume. It was almost as though Daddy was putting a tiny me on top of the tree.

I thought of the night before, and how I’d thought I’d be willing to give up being the angel if only Mother could be home for Christmas, but I couldn’t give up being the angel without upsetting the whole Christmas Pageant, and anyhow, that kind of thing isn’t an offering to God. As our grandfather once told us, you can’t offer anything less than yourself to God; anything less is a bribe, and bribing God is foolish, to say the least. I didn’t really understand all of this. Grandfather’s a theologian, though, and I was sure he was right.

Mother looked at me and said, “What’s the matter, Vicky?”

“Nothing. May I put on some of the breakables this year?”

Suzy was given a box of unbreakable ornaments to go on the lowest branches of the tree. Mother smiled and handed me a beautiful little glass horn that really makes a musical sound. I blew it, and then I let Suzy blow it, too. We all worked together until the tree was shimmering with beauty.

I took a gold glass bell with a gentle tinkle and hung it on the highest branch I could reach. When the last decoration was hung from the tree and we’d all exclaimed (as usual) that it was the most beautiful tree ever, John ran around and turned out all the other lights so that the Christmas tree shone alone in the darkness. We all stood around it, very still, admiring it, and I was peaceful and happy. For a moment I forgot about being the angel. I even forgot about the baby.

On the twenty-third day of December, when I went to the church for dress rehearsal, it finally began to snow. Everybody began to clap and shout with glee, and we kept running to the doors to look at the great feather flakes fluttering from a soft, fluffy sky. Finally the director got cross at us and ordered everyone inside, and Mr. Irving made a big discord on the organ.

In the Sunday school rooms several mothers helped us get into costume. I was dressed early, and Mrs. Irving, who dressed me, said, “Vicky dear, if you stand around here in this mob, your wings are going to get crushed. Go sit quietly in the back of the church until we’re ready to start the run-through.”

I went, holding my wings carefully, through the big doors and halfway down the nave. The church was transformed with pine boughs and candles. The candles wouldn’t be lit until just before the Christmas Eve service, but there was a spotlight shining on the manger. The girl who played Mary came and stood beside me, a high school senior and very, very grown up. She wore a pale blue gown and a deep blue robe. She dropped one hand lightly on my shoulder.

“Some of us thought it was funny, such a little kid being chosen for the angel, and at first we thought you were going to be awful and ruin everything. But Mr. Quinn promised us you wouldn’t, and now I think you’re going to be the best thing in the Pageant, I honestly do.” Then she went and sat by the manger. She sat very still, her head bowed. She didn’t seem like a high school senior anymore. She seemed to belong in Bethlehem. Protecting my wings, I sat down in one of the pews. And for a while, I, too, seemed to be in Bethlehem.

Then the director called out time for the run-through to begin, and everything was hustle and bustle again. The choir in their red cassocks and white surplices lined up for the processional. I was shown into the corner behind the organ, from where I was to make my first entrance.

Everything went smoothly. I even managed to walk as though I had Shu to Sub on my head. My arms felt like curves instead of angles. My words were as bell-like as Mother had been able to make them. At the final tableau I stood by the manger, and I felt shining with joy.

After the choir had recessed and the spotlight had faded on the nativity scene, the director and Mr. Irving congratulated everybody. “It was beautiful, just beautiful!” The mothers who had helped with the costumes and had stayed to watch echoed, “Beautiful! Beautiful!” Except for the fathers, almost everybody who was going to be at church on Christmas Eve was already there.

The director gave me a big smile. “Vicky, you were just perfect. Don’t change one single thing. Tomorrow evening for the performance do it just exactly the way you did today.”

Daddy picked John and me up on his way home from the office. It was still snowing, great, heavy flakes. The ground was already white. Daddy said, “I’m glad I got those new snow tires.”

John said, “You see, Daddy, we are going to have a white Christmas after all.”

When we woke up on Christmas Eve morning we ran to the windows. Not only was the ground white, but we couldn’t even see the road. Mother said the snow plow went through at five o’clock so the farmers could get the milk out, and Daddy had followed the milk trucks, but the road had already filled in again.

We ate breakfast quickly, put on snow suits, and ran out to play. The snow was soft and sticky, the very best kind for making snowmen and building forts. We spent the morning making a Christmas snowman, and started a fort around him. John is good at cutting blocks out of snow like an Eskimo. We weren’t nearly finished, though, when Mother called us in for lunch.

After lunch Suzy said, “I might as well go upstairs and have my nap and get it over with.” We have to have naps on Christmas Eve if we want to stay after the Pageant for the Christmas Eve service. Suzy is very business-like about things like naps. Mother looked a little peculiar, and Suzy went upstairs to bed, taking a book. She can’t read, but she likes looking at pictures. Mother lit the kitchen fire and sat in front of it to read to John and me. We were just settled and comfortable when the phone rang. Mother answered it. We listened.

“Yes, I was afraid of that … Of course … They’ll be disappointed, but they’ll have to understand.” She hung up and turned to John and me.

“What’s the matter?” John asked.

Mother said, “The Pageant’s been called off because of the blizzard, and so has the Christmas Eve service.”

“But why?” John demanded.

Mother looked out the windows. “How do you think anybody could travel in this weather, John? We’re completely snowed in. The road men are concentrating on keeping the main roads open, but all the side roads are unusable. That means that about three quarters of the village is snowed in just like us. I’m sorry about the angel, Vicky. I know it’s a big disappointment to you, but remember that lots of other children are disappointed, too.”

I looked over at the crèche, with Mary and Joseph now in their places, and the manger still empty and waiting for the baby Jesus. “Well, I guess lots worse things could happen.” I thought—If this means Mother will be home for Christmas …

And then I thought—Blizzards can stop pageants, but they can’t stop babies, and if the baby starts coming, she’ll have to go to the hospital anyhow …

“You’re a good girl to be so philosophical,” Mother said.

But I didn’t really think I was being philosophical.

John said, “Anyhow, it looks as though the baby’s going to wait till after Christmas.”

Mother answered, “Let’s hope so.”

John pressed his nose against the window until the pane steamed up. “How’s Daddy going to get home?”

It seemed to me that Mother looked anxious as she said, “I must admit I’m wondering about that myself.”

“But it’s Christmas Eve!” John said. “He has to get home!”

All Mother said was, “He’ll do the best he can. At least I’m the only maternity case on his list right now.”

In all my worrying about Mother not being home for Christmas, it had never occurred to me that Daddy mightn’t be. Even when he’s been called off on an emergency, he’s always been around for most of the time. But if the blizzard was bad enough to call off church, it was maybe bad enough so Daddy couldn’t get up the long steep hill that led to the village.

When it began to get dark, Suzy woke up, all pink from sleep, and hurried downstairs. She was very cross when Mother told her that the Pageant and the Christmas Eve service had been called off. “I needn’t have slept so long after all! And I wanted to see Vicky be the angel!”

Mother answered, “We all did, Suzy.”

Suzy stamped. “I’m mad at the old blizzard.”

Mother laughed. “That’s not going to stop the snow. And remember, you’ve been looking for snow every day. Now you’ve got it. With a vengeance. This is the worst blizzard I remember in years.”

John lit the candle in the window and flicked the switch that turns on the outdoor Christmas tree and the light over the garage door. Then we all looked out the windows. The only way you could tell where the road used to be is by the five little pines at the edge of the lawn, and by the birches across the road. The outdoor Christmas tree was laden with snow, and the lights shone through and dropped small pools of color on the white ground. The great flakes of snow were still falling as heavily as ever, soft and starry against the darkness.

“I guess Daddy’ll have to spend the night at the hospital,” John said.

Mother came to the window and looked over our heads. “No car can possibly get up that road.”

Suzy asked, “What’re we going to have for dinner?”

Mother turned from the window. “I think I’ll just take hamburger out of the refrigerator …” I thought she looked worried.

I stayed by the window.—Please let Daddy get home. Please let Daddy get home.

But I knew Mother was right, and a car couldn’t possibly make it up the road, even with new snow tires and chains.

Love Letters

Love Letters The Summer of the Great-Grandmother

The Summer of the Great-Grandmother A Wrinkle in Time

A Wrinkle in Time The Young Unicorns

The Young Unicorns Two-Part Invention: The Story of a Marriage

Two-Part Invention: The Story of a Marriage The Other Side of the Sun

The Other Side of the Sun A House Like a Lotus

A House Like a Lotus Certain Women

Certain Women Many Waters

Many Waters Camilla

Camilla A Ring of Endless Light

A Ring of Endless Light Meet the Austins

Meet the Austins Dragons in the Waters

Dragons in the Waters The Small Rain

The Small Rain The Moment of Tenderness

The Moment of Tenderness A Wind in the Door

A Wind in the Door Miracle on 10th Street

Miracle on 10th Street The Moon by Night

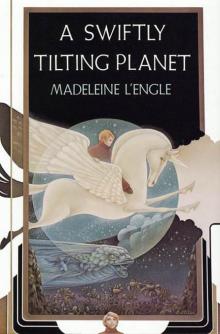

The Moon by Night A Swiftly Tilting Planet

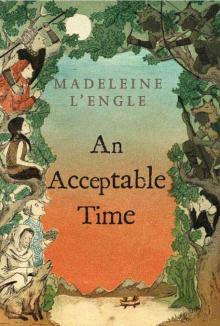

A Swiftly Tilting Planet An Acceptable Time

An Acceptable Time A Severed Wasp

A Severed Wasp The Irrational Season

The Irrational Season A Circle of Quiet

A Circle of Quiet A Live Coal in the Sea

A Live Coal in the Sea Troubling a Star

Troubling a Star Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art

Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art A Wrinkle in Time Quintet

A Wrinkle in Time Quintet Wrinkle in Time

Wrinkle in Time The Wrinkle in Time Quintet

The Wrinkle in Time Quintet Intergalactic P.S. 3

Intergalactic P.S. 3 Walking on Water

Walking on Water Bright Evening Star

Bright Evening Star The Rock That Is Higher

The Rock That Is Higher Madeleine L'Engle Herself

Madeleine L'Engle Herself The Arm of the Starfish

The Arm of the Starfish And Both Were Young

And Both Were Young The Twenty-four Days Before Christmas

The Twenty-four Days Before Christmas And It Was Good

And It Was Good A Stone for a Pillow

A Stone for a Pillow Do I Dare Disturb the Universe?

Do I Dare Disturb the Universe? Sold into Egypt

Sold into Egypt A Wrinkle in Time (Madeleine L'Engle's Time Quintet)

A Wrinkle in Time (Madeleine L'Engle's Time Quintet)